| |

A century later, the most remarkable aspect of Ford Methods and the Ford Shops is the liberal level of access Ford gave to its authors. It is difficult to imagine Google or Apple opening their doors to today’s press and giving unfettered access to employees, workspaces and sensitive production figures. The company’s cooperation speaks volumes about Henry Ford’s confidence in Highland Park. He knew that his methods were far ahead of his competitors, and there was little fear of them catching up too quickly.

|

Workers place magnets on Model T flywheels, 1913. Fittingly, successful experiments with a moving magneto assembly line “sparked” Ford’s adoption of assembly line techniques throughout Highland Park. THF32082

|

The assembly line came to Ford Motor Company in stages. Around April 1, 1913, flywheel magnetos were placed on moving lines. Instead of one worker completing one flywheel in some 20 minutes, a group of workers stood along a waist-high platform. Each worker assembled some small piece of the flywheel and then slid it along to the next person. One whole flywheel came off the line every 13 minutes. With further tweaking, the assembly line produced a finished flywheel magneto in just five minutes.

It was a genuine “eureka” moment. Ford soon adapted the assembly line to engines, and then transmissions, and, in August 1913, to complete chassis. The crude “slide” method was replaced with chain-driven delivery systems that not only reduced handling but also regulated work speed. By early 1914, the various separate production lines had fused into three continuous lines able to churn out a finished Model T every 93 minutes – an extraordinary improvement over the 12½ hours per car under the old stationary assembly methods.

|

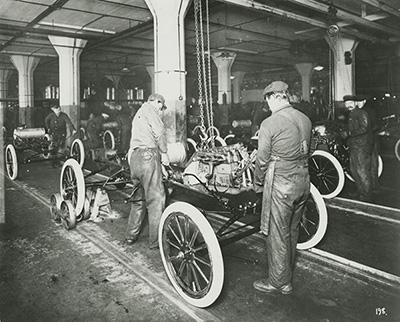

Workers lower an engine into a Model T chassis, 1913. Note that the line is not yet chain-driven. Ford constantly improved the assembly line in search of time and cost savings. THF91696

|

The incredible time and cost savings realized through the assembly line allowed Henry Ford to lower the Model T’s price, which increased demand for the car, which prompted Ford to seek even greater manufacturing efficiencies. This feedback loop ultimately produced some 15 million Model Ts selling for as little as $260 each.

The peak annual Model T production of 1.8 million in 1923 was still years away when Arnold and Faurote made their study. They did not capture Ford’s assembly line in a fully realized form. In fact, the line never was finished. It existed in a state of flux, under constant review for any potential improvements. Adjusting the height of a work platform might save a few seconds here, while moving a drill press might shave some more seconds there. Several such small changes could yield large productivity gains.

Ford Methods and the Ford Shops captures a manufacturer that has just discovered the formula for previously unimagined production levels. The assembly line is groundbreaking, and Ford knows it. The company’s openness with its methods, and Arnold’s and Faurote’s efforts to document and publicize them, helped make the Model T assembly line the industrial milestone that we still celebrate a century later.

| |

-- Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

|

|