| |

Shaping a Public Image

Looking for direct connections with Americans, Kennedy was willing to give them what they craved. This began with his instinctive understanding of the power of television and his unprecedented use of this medium to influence public opinion.

President Kennedy and his family also brought a new spirit and excitement to the nation’s capital. After decades of older Presidential families occupying the White House, this young, handsome family was refreshingly different. Americans were enchanted by the young Kennedy family and they wanted to know more, always more.

Unlike his predecessors—who had only allowed journalists in for succinct, formal photo sessions—President Kennedy invited them into his private life (at least to a point). Photographs of the young President with his glamorous wife Jacqueline and their two attractive children captivated the country, fostering a sense of intimacy between the Kennedys and the American public—and, of course, selling magazines.

Life and Look magazines were the popular documenters of American life at the time of Kennedy’s presidency. Photojournalists from these magazines became particularly well known for their behind-the-scenes photo-essays of President Kennedy and his family. Jacqueline’s charm, grace, and intelligence won over many a critic, but the kids stole the show. Although the First Lady tried her best to keep the children away from the camera lens, the President would on rare occasions let photographers into the room where he was playing with them. These little glimpses into Kennedy’s private life softened the solemnity of international tension and spoke of the perpetual youth and energy that Kennedy embodied.

In an American culture that idolized celebrities like movie stars, sports heroes, and rock ‘n’ roll singers, the Kennedys fit right in. Of course, image wasn’t everything—President Kennedy was an intelligent, solid thinker who sought and achieved results through political means. But image certainly helped. No presidential candidate since that time has been able to discount the importance of the media as an effective tool for creating and reinforcing image.

|

|

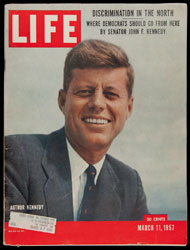

Even before he was President, John F. Kennedy’s youthful image could attract attention and sell magazines. This Life magazine from March 11, 1957 features Senator Kennedy’s article, "Where Democrats Should Go From Here." 2013.84.1 |

| |

|

|

The public was enchanted by exclusive photographs and behind-the-scenes stories of the Kennedy family. The cover story in this Look magazine for February 28, 1961 featured "An exclusive visit with our new first family." 2013.71.1 |

| |

|

|

First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy received a huge amount of media coverage for her restoration of the White House state rooms. The American public was fascinated by Mrs. Kennedy’s sense of style, dedication to history, and determination to authenticate and seek out furnishings used by previous presidents and their families in the White House. This Life magazine, from September 1, 1961, featured a portrait of Jacqueline Kennedy for the cover story, "The First Lady: She Tells Her Plans for the White House." 2013.86.2 |

New Frontier: The Peace Corps

The 10,000 shivering University of Michigan students who awaited Senator Kennedy’s late arrival in Ann Arbor on October 14, 1960, heard about it first. It was 2:00 a.m. after a long day on the campaign trail, and Kennedy—then a Presidential candidate—spoke without a script. In the midst of his brief address, he challenged his youthful audience to consider whether they would be willing to serve their country and the cause of peace by living and working in underdeveloped (now called “Third World”) countries. That night, the idea for the Peace Corps was born.

The response was overwhelming. Within weeks, hundreds of students signed petitions and pledged to serve. Enthusiastic letters of support poured into Democratic Headquarters. This initial public reaction was crucial to Kennedy’s decision to make his Peace Corps a reality.

It was not a new idea. But Kennedy recognized it as an opportunity to advance his vision of young Americans becoming “pioneers” in his “new frontier,” spreading hope and goodwill among people all over the world. Furthermore, Kennedy believed that this could serve as a new weapon against the Cold War, the non-military conflict that engendered Americans’ fear that the Soviet Union would spread communism throughout the world.

Despite skepticism by some members of Congress, President Kennedy issued an executive order establishing the Peace Corps as a pilot program on March 1, 1961. He named his brother-in-law Sargent Shriver as its first director, who proceeded to quickly give distinctive shape to the program.

President Kennedy’s founding of the Peace Corps was not without its critics. But it is one of his most enduring legacies. It continues to operate today, attracting people who feel the kind of civic responsibility that President Kennedy inspired.

|

|

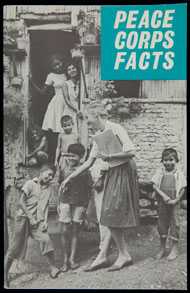

The United States government published this booklet and information request form in 1964. On its pages, interested people could learn more about the Peace Corps program and how they could contribute to it. Images of happy Peace Corps volunteers, like the one depicted on the cover of this booklet, likely contributed to the huge response that year. 2013.65.1 |

New Frontier: Outer Space

Like the Peace Corps, Kennedy’s vision to explore the “new frontier” of outer space was an overt Cold War strategy. The Space Race had begun back in the late 1950s, when both the United States and the Soviet Union had attempted to launch ballistic missiles into outer space. Americans were surprised when the Russians beat them to it, launching the Sputnik I satellite in October 1957. When Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin orbited earth on April 12, 1961, Americans were downright shocked—and not a little concerned. As a response, President Kennedy pledged to support an American space program that would eventually dwarf the Soviet program in technological achievement.

Three weeks after astronaut Alan Shepard became the first American in space on May 5, 1961, Kennedy delivered a “Special Message to Congress on Urgent National Needs.” Here he laid out a dramatic and ambitious plan: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before the decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” This was a bold move, one which up until that time had seemed like science fiction! Of course, Congress had to approve a massive budget increase for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to make this even a remote possibility.

Like the Peace Corps, Kennedy’s vision for his new Space Program ignited the public’s imagination. On February 20, 1962, Americans celebrated as astronaut John Glenn became the first American to orbit the earth. Kennedy called Glenn’s flight “a magnificent achievement.”

Other flights followed after Kennedy’s presidency, despite criticism that exploring outer space was less important than solving social problems at home. But finally, on July 20, 1969—just six months before the end of the decade—American astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to set foot on the moon. To many people, the 1969 moon landing, first envisioned by President Kennedy back in 1961, was America’s finest hour.

|

| Souvenirs helped generate excitement about the latest achievements in the space program. This pictorial card depicts President Kennedy awarding NASA's Distinguished Service Medal to America’s first astronaut, Navy Commander Alan B. Shepard, Jr. on May 8, 1961, three days after his successful flight. 2013.54.1 |

|

|

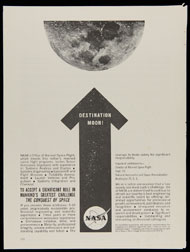

This recruiting advertisement for NASA appeared in the July 1962 issue of Scientific American. It was one in a series of ads intended to convince senior aerospace engineers "to accept a significant role in mankind's greatest challenge--the conquest of space." 2013.52.4 |

|

| For children in the 1960s, the idea of space flight was wondrous. This souvenir bank, of copper-colored plastic in the shape of a space capsule, commemorated the U.S. space flights of astronauts Alan B. Shepard (May 5, 1961) and John H. Glenn (February 20, 1962). For parents, it had the added value of encouraging children to save money. 2013.57.1 |

| |

-- Donna R. Braden, Curator of Public Life

-- Cynthia Read Miller, Curator of Photographs and Prints

-- Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

|

|