| |

Separate and Unequal

“Jim Crow” laws—first enacted in the 1880s by angry and resentful Southern whites against freed African Americans—separated blacks from whites in all aspects of daily life. Favoring whites and repressing blacks, these became an institutionalized form of inequality.

|

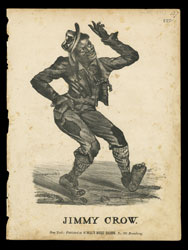

|

Jim Crow was a character created for a minstrel-show act during the 1830s, the date of this sheet music. The act—featuring a white actor wearing black makeup—was meant to demean and make fun of African Americans. ID 00.4.945. |

In the Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states had the legal power to require segregation between blacks and whites. Jim Crow laws—now legally enforceable—spread across the South virtually anywhere that the two races might come in contact. Many of these practices lasted into the 1960s, until outlawed by the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

|

|

| Through separate (and inferior) public facilities like building entrances, elevators, cashier windows, and drinking fountains, African Americans were reminded everywhere of their second-class status. ID 2005.19.1 and 2005.19.2. |

Travel in the segregated South was particularly humiliating for African Americans, beginning with railroads back in the 19th century. Traveling in or between southern states by railway, African Americans of all economic classes were generally relegated to primitive, uncomfortable “Jim Crow cars”. Located just behind the locomotive, these were also the most dangerous cars should a collision or boiler explosion occur. Any black railway passenger who complained or refused to comply with the rules could be forcibly removed from the train, beaten, or even killed. Conductors in some states were given policing power to enforce the rules or they could summon local police at station stops to back them up.

|

| Southern states established segregated railroad station facilities for blacks, with separate (and often inferior) ticket agent windows and restrooms, and often lacking the eating facilities available to whites. This sign was installed in a Louisville & Nashville Railroad station. ID 89.210.1. |

The coming of affordable automobiles seemed to provide southern blacks with a way to get around the indignities of long-distance rail travel. However, as soon as black motorists stopped along the road, Jim Crow laws returned in force. Service station and roadside restrooms were usually closed to African Americans, so they often resorted to stashing buckets or portable toilets in their trunks. Diners and restaurants regularly turned away black customers, who took to bringing food along with them. Roadside motels often refused to admit blacks, so they had to depend on the hospitality of their own people or chance the discovery of a “Negro” rooming house.

|

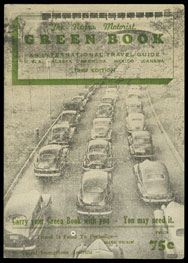

|

To avoid Jim Crows laws while travelling in the South (and unwritten Jim Crow practices followed in the North), black motorists created their own tourist infrastructure, with specially published guides steering them to safe accommodations. This is the 1949 edition of “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” produced by postal employee Victor H. Green, of Harlem, New York, from 1936 until the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964. ID 87.135.1736. |

Physically separating blacks and whites was most difficult on city transit systems. By 1905, every southern state had outlawed blacks from sitting next to whites on trolleys and streetcars, while individual conductors usually ordered black patrons to move from this or that seat. Middle-class blacks were particularly indignant about these laws and organized numerous long-forgotten boycotts and protests. But, like railroad conductors before them, streetcar conductors were given policing power—and even weapons—to enforce the laws. Any blacks who challenged the rules of behavior were dealt with swiftly and harshly.

As buses replaced trolleys and streetcars on city streets, Jim Crow laws continued. Each state and city had different requirements and customs to signal how blacks and whites were to be separated on the buses. But, as with earlier modes of transportation, individual drivers had great latitude in determining where people sat and the power to enforce their decisions.

By the 1950s, as many as 40,000 African Americans regularly rode the city buses in Rosa Parks’ home town of Montgomery, Alabama (compared with about 12,000 whites). Officially, ten seats in the front of each bus were reserved for whites. These spaces were reserved no matter what. Often this meant black riders were jammed in the aisle, standing over empty seats. If the white section filled up and more white riders came in, an entire row of black passengers had to get up and move back. Bus drivers could demand more seats for whites at any time and in any number. Furthermore, drivers often forced African-American riders, once they had paid their fare, to get off the bus and re-enter through the back door—sometimes driving away without them. (Rosa Parks had actually experienced this.) Those who didn’t comply with these rules could be not only verbally abused but also slapped, knocked on the floor, pushed out the door, beaten, or even killed (which did occur in a few little-publicized cases).

A Courageous Act

As stories of abusive drivers and humiliating incidents continued to spread, anger in the black community grew. However, most of the time, the indignities went unchallenged. Expecting African Americans to resist these long-established laws and traditions meant asking them to risk great harm and to summon an extraordinary amount of personal courage.

By 1955, inspired by attempts in other cities, black community leaders in Montgomery explored the idea of a city-wide bus boycott—an organized refusal to use the buses. But they would need the united support of the city’s African-American bus riders, a notion that was unprecedented, untested, and likely to fail given past experience. And, after some fits and starts in trying to find an appropriate test case, they realized that a successful boycott would require the determined action of someone who possessed a flawless character and reputation and, at the same time, could ignite the action of an entire community.

That person, it turned out, was Rosa Parks. Her action on December 1, 1955, was unplanned and spontaneous, although her life experiences had undoubtedly prepared her for that moment. She was not the first African American to challenge the segregation laws of the Montgomery city bus system. But her sterling reputation, her quiet strength, and her moral fortitude caused her act to successfully ignite action in others.

|

This Montgomery city bus, acquired by The Henry Ford in 2001, is the actual bus on which Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat back in 1955. It now resides in Henry Ford Museum’s With Liberty & Justice For All exhibition.

ID 2001.154.1. |

Sparking a Movement

Rosa Parks’ arrest for defying the Jim Crow law of segregation on Montgomery buses led to an immediate city-wide bus boycott, during which the black community shared rides, walked, or worked out carpools—despite burnings, bombings, gunshots, and arrests. The Montgomery bus boycott lasted more than one year—381 days to be exact—until the U.S. Supreme Court finally declared segregation on Alabama buses to be unconstitutional.

Rosa Parks’ simple, courageous act gave African Americans everywhere a new sense of pride and purpose, and inspired non-violent protests in other cities. Because of this, many consider her singular act of protest on the bus to be the event that sparked the Civil Rights movement.

Unfortunately, the impact of her act took its toll on Rosa Parks herself. She lost her job, her marriage became strained, her quiet life was gone, and she received threatening phone calls and letters. In 1957, she left Montgomery, moving to Detroit and eventually working for Congressman John Conyers.

How did Rosa Parks summon the courage to defy decades of established rules and traditions about segregated travel? A few months after her arrest, she explained it like this:

The time had just come when I had been pushed as far as I could stand to be pushed, I suppose. I had decided that I would have to know, once and for all, what rights I had as a human being, and a citizen, even in Montgomery, Alabama.

Listen to Rosa Parks' Quotation

| Audio excerpt from Rosa Parks Bus presentation in Henry Ford Museum. Original 1956 radio interview with Rosa Parks from the collections of Pacifica Radio Archives. (archive no. BB0566) |

Rosa Parks was not a civic, political, or religious leader. She was just an ordinary person. And she well knew the risks of her actions. But, through her example, she showed others what was possible. Her uncommon courage shines through as an inspiration to us today.

| |

-- Donna R. Braden, Curator of Public Life

|

|