| |

Inspired to Take a Stand

|

|

|

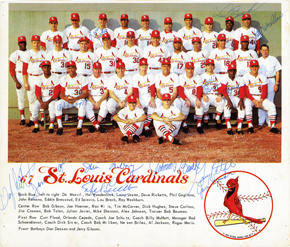

| The St. Louis Cardinals defeated the Boston Red Sox to win the 1967 World Series. This team photo is signed by many of Flood’s teammates, as well as some Red Sox players. ID.THF76598 |

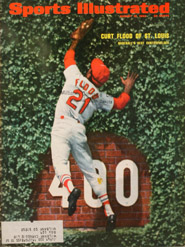

Curt Flood was featured on the cover of the August 19, 1968 issue of Sports Illustrated, which called him, “Baseball’s Best Centerfielder.” ID.THF76591 |

|

Curt Flood grew up in Oakland, California, and had no direct experience with the intense racism of the Jim Crow South. He was among the first generation of African Americans to play in Major League Baseball. In 1956, as a 19-year-old minor leaguer in the Deep South, Flood came face-to-face with the virulent racial hatred that had arisen in the wake of the 1955 Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation in schools, and from the ongoing Montgomery Bus boycott inspired by Rosa Parks. It was the courage shown by Jackie Robinson, the first African American to play in the Major Leagues, Rosa Parks, and others that gave Flood the strength to persevere through his two-year minor league stint.

Flood joined the Major Leagues when he was signed by the St. Louis Cardinals in 1958. He and two of his new teammates, African-American players Bill White and Bob Gibson, became increasingly outspoken about segregationist aspects of the Cardinal operation. These men successfully pressed the organization to patronize integrated hotels and restaurants. Flood also joined Jackie Robinson at NAACP rallies across the South.

Fighting the Reserve Clause

Flood’s stellar 12-year career with the Cardinals ended suddenly in 1969, when he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies. The Phillies were a team going nowhere, with a fan base and management that were hostile to African-American players--Flood had little desire to be part of that team. But the reserve clause gave Flood no choice in the matter. This clause was a standard part of every baseball player’s contract, requiring him to play wherever the owners wanted him to play. The baseball player had no say in the matter.

Flood’s only options were to go along with the trade or retire. His first instinct was to retire. But, after reconsidering, he decided to challenge the reserve clause and sue Major League Baseball. Flood knew that this action would, in effect, end his baseball career and that he personally would gain little in the end. But the reserve clause made Flood feel like a piece of property--and he could not let that injustice stand.

Curt Flood’s letter to Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn was brief and to the point:

Dear Mr. Kuhn:

After twelve years in the Major Leagues, I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several States.

It is my desire to play in 1970, and I am capable of playing. I have received a contract offer from the Philadelphia Club, but I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decisions. I, therefore, request that you make known to all the Major League Clubs my feelings in the matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.

Sincerely yours,

Curt Flood

Lonely Path to the Supreme Court

|

|

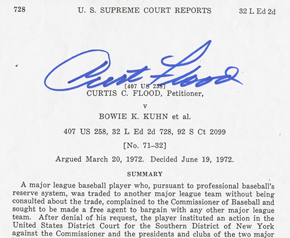

| Curt Flood signed this copy of the Supreme Court summary report of his suit against Major League Baseball. ID.THF76595 |

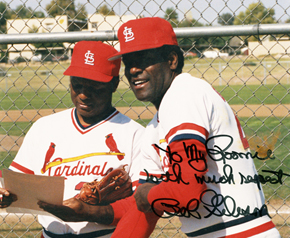

Curt Flood (left) and pitcher Bob Gibson, had been close friends since their days in the minor leagues. Gibson privately supported Flood in his activism, but in spite of being one of the best pitchers in the game, he feared backing Flood publicly would put him on baseball’s blacklist. ID.THF76597 |

As expected, Major League Baseball rejected Flood’s request. Over the next two and a half years, Flood, with the support of Marvin Miller of the Players Association, the fledgling players’ union, pursued his case in court, then in appeals court, and finally, to the United States Supreme Court. At the inception of the suit, Flood quickly became one of the most hated men in baseball--he was criticized in the press for trying to destroy baseball, and received mountains of hate mail from fans. But it was the lack of support from active players that hurt Flood the most. Some supported Flood privately, but feared retribution if they spoke out. Others were outright hostile and tried to undermine the suit despite the fact that the suit would benefit all players. It was only baseball outsiders who testified on Flood’s behalf: his hero, Jackie Robinson; Hank Greenberg, who battled anti-Semitism throughout his career with the Tigers; and the iconoclastic Bill Veeck, who had owned several major and minor baseball teams.

The court battles took a physical and emotional toll on Flood. He fell out of shape physically and turned from a social drinker to an alcoholic. The relentless negative attention from the press and fans forced Flood out of the country, first to Denmark, and later to Spain. He lost touch with his children, and by 1975, was nearly destitute and homeless. Flood was despondent and depressed. In 1978, Richard Reeves interviewed him for Esquire magazine as part of a series on men who had stood up to the system. Reeves said, “He was about the saddest man I ever met.”

The closely-divided Supreme Court ruled against Flood in the end. The majority opinion said, in effect, that the reserve clause was “an anomaly,” but that it was Congress’s job to fix it, not the courts. Despite losing in the Supreme Court, Flood’s fight had created an opening to challenge baseball’s reserve clause on the bargaining table. Within a few years, Jim “Catfish” Hunter became the first free agent, followed closely by Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally. While Curt Flood lost the case, his efforts transformed the relationship between owners and players across professional sports, and for people with unique and valuable skills in the world at large.

Recovery and Recognition

|

|

| In 1987, the NAACP recognized Curt Flood’s fight by awarding him the Jackie Robinson Sports Award. ID.THF76582 |

Curt Flood and his wife Judy Pace Flood with Rosa Parks in 1994. ID.THF76600 |

After more than a decade in a personal wilderness, Flood began to turn his life around with the help of friends. He was treated for alcoholism in 1980, re-married in 1986, gained a new family and reconnected with the children of his first marriage. Flood took up the late Jackie Robinson’s cause --pushing for more African Americans in the management of baseball and, with 60 former African-American players, formed the Baseball Network for that purpose.

In 1987, Curt Flood received the NAACP Jackie Robinson Sports Award. While he was never able to get a job in baseball, Flood became a regular at the old-timers games. There, many former players took the opportunity to thank him personally. In 1994, Flood was featured in Ken Burns’s Baseball documentary and attended the premiere, where he also met President & Mrs. Clinton. Not long after, he met another hero from his youth--Rosa Parks, who signed a baseball for him. Flood wrote to friends in a Christmas letter that year, “I am in the process of living happily ever after.”

In the summer of 1995, Flood developed throat cancer and died January 20, 1997. During that year and a half, many people visited him to express their gratitude for what he had done for baseball and for society at large. At his death, Curt Flood was eulogized by many, including Jesse Jackson and conservative columnist George Will, who compared him to Rosa Parks.

While, in retrospect, it seems like changes in society are predetermined and expected, Curt Flood’s experience shows that they are not a sure thing--and they are never easy. The reserve clause was a legal anachronism that stripped players of their freedom to control their own careers. Yet it took a very successful man--inspired by heroes who had taken similar steps before him and who was willing to give up everything for the cause--to make that change occur.

|