|

|

| |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

MORE |

|

ID 2000.32.58 |

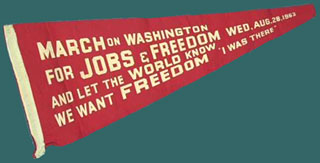

Long-time civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph had proposed a public civil rights march on Washington as early as 1941. President Franklin D. Roosevelt forestalled that march by issuing a wartime executive order outlawing segregation in defense industry employment practices and establishing the Fair Employment Practices Commission. However, 1963 was a different matter. Racial turmoil had been common since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that “separate but equal” was unconstitutional in the 1954 case of Brown v. Board of Education. Protests had focused international attention on cities such as Montgomery, Alabama, Albany, Georgia and Little Rock, Arkansas. In 1963, the nation was shocked to see police dogs and fire hoses unleashed on civil rights marchers in Birmingham, Alabama. Then Alabama governor George W. Wallace defied federal law and blocked the entrance of black students to the University of Alabama. President John F. Kennedy took action. Kennedy made a nationally televised speech on the evening of June 11. He focused on civil rights: “The fires of frustration and discord are busy in every city. Redress is sought in the street, in demonstrations, parades and protests which create tensions and threaten violence. We face, therefore, a moral crisis as a country and as a people.” He went on to propose a new civil rights bill that would end segregation in interstate public accommodations, permit federal lawsuits to integrate schools and cut off federal funds to segregated schools. Leaders of the major civil rights groups immediately announced that they would march on Washington in support of this new civil rights legislation. The leadership group included A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Roy Wilkins of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Martin Luther King, Jr., of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and Whitney Young of the Urban League. Activist Bayard Rustin was assigned to organize the march. In less than 60 days he made all the local arrangements in Washington and prepared more than 2,000 community leaders with the information they needed. Hundreds of thousands of official pins and banners were sold to help offset the cost of the march. Labor unions and religious groups joined with civil rights leaders in promoting the march. Politicians and Washington officials feared mass rioting that would destroy the nation’s capital. Unity, racial harmony and “Pass the Bill” became the themes of August 28, 1963. Organizers hoped for 100,000 marchers. In the end, more than 30 special trains and 2,000 chartered buses brought 250,000 civil rights advocates to Washington, almost a quarter of them whites. It was at the time the largest demonstration for human rights in the nation’s history and a peaceful one at that. Songs at the Washington Monument were followed by speeches at the Lincoln Memorial. Roy Wilkins stunned the assembled multitudes by announcing that Dr. W.E.B. DuBois who, “at the dawn of the twentieth century . . .was the voice that was calling to you to gather here today in this cause,” had died earlier that very day in Ghana. Martin Luther King, Jr. concluded the day’s public speaking with his “I Have a Dream” speech. It electrified the crowd, impressed President Kennedy and has gone down in history as one of the finest speeches of the modern age. We have not heard public oratory that impressive in the forty years since.

|

| Copyright © The Henry Ford ~ http://www.TheHenryFord.org |