| |

There is a web of connection between all three of these artifacts: a Telegraphone wire recorder, a radiophone transmitter for aircraft, and an optical MASER from Bell Laboratories. Most simply, all three devices can be used to capture and transmit human speech. All three have the ability to take the words from your mouth, transform them into data, and reassemble them in another location, or onto a different medium. All three are launching points towards other technologies that remain in use today.

These artifacts are also far-flung alternatives that were meant to challenge whatever was “standard” at the time. Thomas Edison’s wax cylinder recordings were well dispersed by the 1890s, but the wire-based Telegraphone attempted an entirely different medium. And, a fateful chance encounter with the wire recorder’s later cousin, the Magnetophone, led to game-changing moments in American broadcast history. George Squier established first schools to teach U.S. Army troops to quickly decode Morse code, but he also invented an aircraft radio that could exchange direct messages through the human voice, cutting out the need to translate all of those dots and dashes. And finally, the telephone had become widespread by the early 1900s, and was a relatively stable technology, but the attitude at Bell Labs at mid-century was to push boundaries, and so they experimented with using the optical MASER as a communication device.

Telegraphone Wire Recorder (c.1908-1914)

|

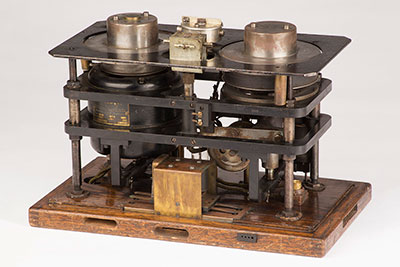

| Telegraphone used by the United States Navy, 1908-1914. Invented by Valdemar Poulsen and manufactured by the American Telegraphone Company. The round posts at the top would have held spools of wire for recording. THF157875 |

The Telegraphone (or telegrafoon in its native Danish), was invented by Valdemar Poulsen between 1898 and 1900. It was the first device capable of producing magnetic recordings. In 1900, while demonstrating his invention at the World Exposition of Paris, Poulsen recorded the equivalent of the modern-day “sound bite,” capturing the voice of Austria’s Emperor, Franz Joseph. You can still listen to this, the oldest surviving magnetic recording. Translated from German, Franz Joseph tells the listener: “I found this invention very interesting and I thank you for its demonstration.” The Telegraphone’s spools held thin magnetized steel wire—this is what held the sound—which could be used more than once to play back, erase, and re-record. The wire contained on the reels of the Telegraphone had to be thin, because it took 24 inches per second to record audio.

|

Control Unit for a Telegraphone wire recorder by the American Telegraphone Company, circa 1905. This rare component had the ability to start and stop the main unit. The indicator dial on the face allowed the user to see how much wire was left for recording. THF156737 |

In 1903, The American Telegraphone Company purchased the rights to Poulsen’s patents and began manufacturing these machines for the commercial market. They advertised the potential use of Telegraphones as scientific instruments, music recording devices, telephone answering machines, and office dictation systems. This particular machine was used by the US Navy to record the code signals of wireless transmissions. The Telegraphone was short lived, however, because it was in competition with dictation devices like the Ediphone and Dictaphone. Ultimately, the sound fidelity of wire recordings, which had a tendency to twist and warp sound upon playback, couldn’t compete with the reliability and ease of use of the wax cylinders used in Ediphones.

|

| Thomas Edison is seen here in an automobile, using the machine that competed with and ultimately succeeded over the Telegraphone—a dictation device with wax cylinders. THF230855 |

But the Telegraphone’s legacy continued. In 1928, an engineer named Fritz Pfleumer expanded upon Poulsen’s idea for wire recordings, replacing the wire with thin paper tape coated with iron oxide powder. Two years later, a collaboration between the German companies AEG and BASF refined Pfleumer’s ideas, using a new material: thin plastic tape coated with magnetic pigment.

|

| A typical reel-to-reel magnetic audio recording tape, manufactured by Ampex. THF325420 Gift of Robert H. Casey. |

Jack Mullin, a member of the U.S. Signal Corp, was excited about the quality of these large Magnetophones, and so “liberated” a few from bombed out German radio stations. According to military rules, anything sent home as a war souvenir had to fit into a standard mailbag. So, Mullin broke the large machines down into 35 pieces, and reassembled them in the United States. Once home, he demonstrated the Magnetophone for engineers from the Ampex Corporation, who were able to improve upon its design. These prototypes of the Ampex 200A were brought to radio and television stations, but most were dubious of the finicky technology. Eventually, Mullin and Ampex caught the ear of Bing Crosby at ABC. Crosby was tired of having to repeat his radio performances for Eastern and Pacific time zones—he placed an order for 20 machines at the cost of $4000 each, effectively launching the adoption of taped radio performance in America. While Mullin is not a household name, Bing Crosby is far from an unknown. These two men, by total chance, became entangled with pioneering changes to broadcast history—albeit one that has a somewhat convoluted history of iteration.

Model SCR-67 Radiophone Transmitter and Receiver (1918)

|

| Western Electric Radiophone, Model SCR-67, c. 1918. THF156561 |

In 1918, while serving as the Chief Officer for the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps, General George Owen Squier contributed work that was instrumental to aircraft communications. At the time, the reception of messages relayed between aircraft and ground radio operators was lacking—airplanes were loud and drafty, making them a less than ideal environment for clear transmissions. The SCR-67 (for ground use) and SCR-68 (airborne) radio units changed this. Produced through a collaborative effort between Squier, the Signal Corp and Western Electric engineers, these radiotelephones not only resulted in an easier exchange of information between pilots and ground operators—they also allowed controllers to direct precise formation flying, acrobatics, and to guide airborne gunfire.

But Squier’s work with the SCR radiophone is only one aspect of his remarkable career. In the 1890s, while working towards his PhD in electrical science at Johns Hopkins, he conducted experiments to detonate and fire artillery via remote control. In the early 1900s, he established the first Signal Corps school, where military radio operators learned to decode Morse code messages. Squier received several patents related to multiplexing telephony in 1909—a concept that is integral to the modern communication age. Multiplexing allowed multiple voice messages to be sent over a single wire and in modern terms, is integral to things like networked computers—and organizing the flow of data that allows that little thing called the Internet to flow smoothly. One of the more intriguing patents Squier received was for “Tree Telephony.” By hooking antenna wires into a tree (preferably oak, and in full foliage), the inventor realized that he could listen to broadcasts being issued from the powerful Nauen, Germany wireless station.

|

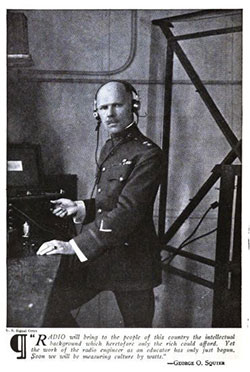

General George Owen Squier was often featured in enthusiast magazines for radio. The October 1922 issue of Popular Radio featured this image. The caption reads: “Radio will bring to the people of this country the intellectual background which heretofore only the rich could afford. Yet the work of the radio engineer as an educator has only just begun. Soon we will be measuring culture by watts.” |

It is important to note that before the United States entered World War I, communicating in the field via radio occurred through Morse code. The field radios that allowed soldiers on the ground to communicate with one another were cumbersome to transport, assemble, and knockdown. It took up to three pack mules to transport one radio. The inconveniences of this form of communication in grimy battle situations pushed Squier to use his knowledge of electrical engineering. He first improved radio communication by perfecting military radio tubes, creating standardized, rugged, and reliable alternatives. Squier wasn’t shy in collaborating with established companies in the communication industry; his symbiotic work that joined the military with large communications businesses is one area in which he excelled.

Next, he founded a research and development laboratory at Camp Alfred Vail in New Jersey, an intensive training site for signal troops. Radio intelligence operators at Vail not only learned to quickly intercept messages (in English and foreign languages)—they also worked with the analog technology of the carrier pigeon. His staff of radio operators and engineers grew into the hundreds. It was out of this laboratory that the revolutionary SCR-67 and 68 emerged. These radios were celebrated for their ability to transmit the human voice—a much more immediate way to receive information, rather than dots and dashes of Morse code.

When World War I ended in November 1918, Squier’s work on the SCR radiophones was absorbed and modified for use in other military radio equipment. But the end of the war didn’t stop Squier’s life in invention. In the 1920s, he received a series of patents related to something called “Wired Radio.” His idea was that, using existing electrical lines, business owners could receive piped-in music in their stores. They would pay a subscription fee, and endless music would fill their shops through a wooden box provided by Squier. Intrigued with the made-up word of “Kodak,” he combined “music” with “Kodak”—and Muzak was born.

|

The patent for a “Radio Signaling Device” by George Owen Squier, detailing his ideas behind “Wired Radio”—which would later become known as Muzak. U.S. Patent 1791541A. |

Muzak is something we now equate with the sappy, soothing music heard in public spaces: department stores, offices, and grocery stores. Muzak is polite—it doesn’t intrude—but recedes into the background, creating a mind-numbing palette of sound. What we think of when we hear the word Muzak—that type of music is developed out of research and (supposedly) carries a psychological effect called “stimulus progression.” Easy listening sounds built up in rhythm and intensity over the course of 15 minutes – the general linger time of a shopper, or the time it took a worker to perform an average task. Over time, Muzak tried to align itself as a form of time and labor management, taking cues from Frederick Winslow Taylor’s 1911 classic, Principles of Scientific Management. This phase of Muzak occurred well after Squier sold his rights to the invention. While the wooden box is now our computer, digital music subscription services like Pandora and Spotify share historical lineage with “wired radio.”

Bell Laboratories Optical Maser (1963)

|

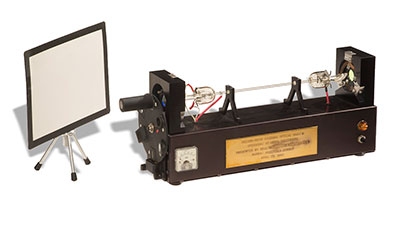

| The Helium-Neon Gaseous Optical Maser presented to The Henry Ford by Jack Morton of Bell Laboratories in 1963. This is a rare working demonstration model. THF156641 |

In 1960, Ali Javan and William Bennett—two researchers at Bell Telephone Laboratories in Murray Hill NJ—invented the first helium-neon gas “MASER.” The word MASER itself is likely a mysterious one; it is an acronym for “Microwave Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation.” Years later, when the word “Microwave” was replaced by “Light,” and the much more familiar term of laser emerged. In a nutshell, the helium-neon gas maser operates by moving electrical energy through gas. When the two collide, a reaction occurs, and the resulting energy is converted into intense light.

Optical masers produce concentrated, clean, and sharp beams of light—the type of light that could serve well as a noise-free information carrier. A 1963 educational film produced by Bell Labs, Principles of the Optical Maser claims that “a single maser beam might reasonably carry as much information as all the radio-communication channels now in existence.” Javan recognized this potential too. By December 1960, he took part in the first telephone conversation using lasers as carriers for human speech: “I heard a voice, somewhat quivering in transmission, telling me that it was the laser light speaking to me.”

The optical maser did in fact influence the groundwork for the early days of fiber optic communications—the backbone of today’s Internet. As the helium-neon maser took hold in the commercial market, it could be seen at work through barcode scanners, laser-disc players, computer printers, holography, and monitoring technologies in the medical and military field.

Jack Morton, vice president of electronic technology at Bell Labs, personally presented a rare working model of the helium-neon gas maser to The Henry Ford Museum in 1963. The first transistors—pervasive devices that power everyday life in the digital age—were transformed into viable products under Morton’s leadership at Bell Labs in the late 1940s and early 1950s. At the April 1963 meeting of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers’ meeting held at Henry Ford Museum, audience members were treated to a selection of scientific films created by Bell Labs and a lecture by Morton, “Cracking the Numbers Barrier in Electronics.”

Included with the maser was a set of instructions for its operation. General Instruction #1? Never look directly into the maser beam.

| |

-- Kristen Gallerneaux, Curator of Communication & Information Technology |

|