Heritage

HeritageGame Changer: Ford Celebrates 100 Years of the Moving Assembly Line

Published: Sept. 27, 2013

The $5 Work Day

If the development of the moving assembly line was Henry Ford’s claim to fame in eyes of industrialists, manufacturers and business men, then establishing the $5 per day wage was his way of guaranteeing its success.

378 Percent Turnover Rate

Without a doubt the moving assembly line, as it applied to the automotive industry, represented a monumental advancement in production capabilities and potential earnings. Mass production of automobiles also drove down the cost of each vehicle, making vehicle ownership a reality for more people.

However, in order to optimize the assembly line, a stable workforce was needed that could be trained and then relied upon to fulfill their assigned tasks on a daily basis. In the early days of automotive production, a high rate of turnover (as much as 378 percent, or 53,000 employees per year, according to Henry Ford in his book, My Life and Times) kept manufacturing facilities from meeting production goals. As a result, Ford and his team placed significant effort into studying other manufacturing facilities in search of ways to secure staffing.

Landmark Annoucement: The Middle Class Emerges

Ultimately, to put an end to production losses, months after establishing the moving assembly line Henry Ford made a decision that shocked many of his auto-industry peers while simultaneously spreading hope to thousands of average citizens. Henry Ford raised the base pay of plant workers from $2.34 for a nine hour day to $5 for an eight hour day.

Just as the moving assembly line changed the business model for building cars, this change in pay made a drastic and lasting impression on society. The $5 work day drew workers from around the world, helped build the middle class, and fostered “The Great Migration” of workers from the south to the industrial mid-west – all activities cemented into the history books school children still study today.

Game Changer

Ford celebrates the 100th anniversary of the innovation that made the greatest impact on manufacturing, industry and society as a whole: the moving assembly line.Impact of a Big Idea

Not only did the moving assembly line drastically increase the pace at which cars were produced, it also drove down the price of each car making them more accessible to the masses.

Bringing the product to the worker instead of moving various teams of workers to the product became the idea that overhauled the manufacturing industry as a whole. A new standard had taken over making it possible to generate more products and greater income through mass production.

How it Began

When Henry Ford began making cars in the early 1900s, “state-of-the-art” manufacturing meant car bodies delivered by horse-drawn carriage, with teams of workers assembling automobiles atop sawhorses. The teams would rotate from one station to another, doing their part to bring the vehicle together. Parts deliveries were timed, but often ran late causing pile-ups of workers vying for space and delays in production. Fortunately for the future of industry, these archaic practices came to an end Oct. 7, 1913.

Observers of the time were already suggesting that someone needed to invent a way to mass produce cars, and by doing so bring down the price to enable more people to afford the luxury. J.J. Seaton wrote in Harper’s Weekly in January 1910 that “the man who can successfully solve this knotty question and produce a car that will be entirely sufficient mechanically, and whose price will be within the reach of millions who cannot yet afford automobiles, will not only grow rich but will be considered a public benefactor.”

Car for the Masses

Ford already had developed in 1908 the Model T, a “car for the masses.” Now it was time to find a way to make many of these cars at a rapid pace and with high quality. Ford surrounded himself with experts from various fields, such as brewing, canning and steel making, and each contributed his expertise to a solution for mass auto manufacturing. Ford’s vision and leadership enabled him to create a climate where his team could collaborate, bring new ideas and bring forward several factory innovations that ultimately led to the development of the moving assembly line.

A Revolution is Sparked

On Oct. 7, 1913, Ford’s team rigged a rudimentary final assembly line at the Highland Park Assembly plant. Engineers constructed a crude system along an open space at the plant, complete with a winch and a rope stretched across the floor. On this day, 140 assemblers were stationed along a 150-foot line and they installed parts on the chassis as it was dragged across the floor by the winch. Man hours of final assembly dropped from more than 12 hours under the stationary assembly system to fewer than three. In January 1914, the rope was replaced by an endless chain.

By bringing the work to the men, Ford engineers managed to smooth out differences in work pace. They slowed down the faster employees and forced slower ones to quicken their pace. The results of mass production were immediate and significant. In 1912, Ford Motor Company produced 82,388 Model Ts, and the touring car sold for $600. By 1916, Model T production had risen to 585,388, and the price had dropped to $360.

“Fordism” – large-scale production combined with high wages – was born and spread to other industries around the world. Soon, even small automobile companies producing only a few hundred cars per year were attempting to install moving assembly lines.

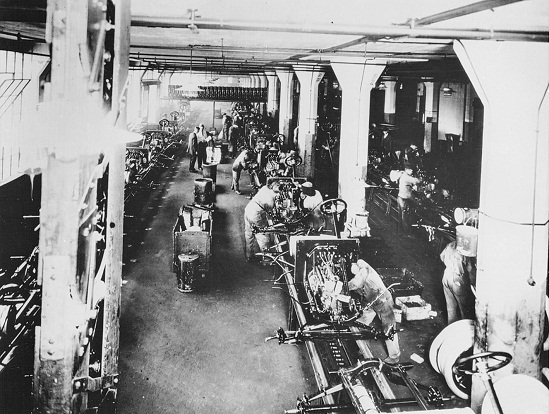

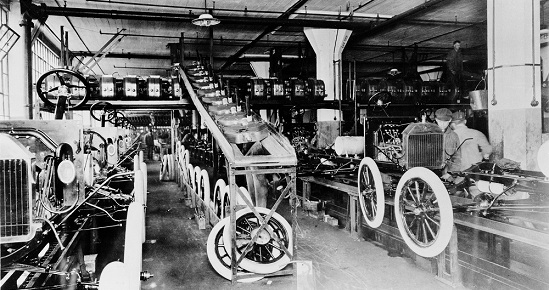

The Story in Pictures: Birth of Large-Scale Production

Early Model T

Early Model T assembly at Highland Park Plant.

10 Millionth Model T

Thanks to the moving assembly line, Ford was able to produce the 10 millionth Model T by 1924.

Exponential Growth

As the company expands, plants like this one in Dallas, Texas, sprout up around the world.

Refining the Process

Increased Complexity

By 1941, the vehicles coming down the line had changed significantly, adding elements of complexity to the assembly line.

Make Way for Mercury

A line of Mercury models reaches the final assembly stage in 1946.

Engine Inspection

A Ford crew inspects an engine circa 1946.

Dearborn Assembly

Dearborn Assembly Plant in 1954.

Pre-Ergonomic Plant Design

Before ergonomic design made its way into the plants, some workers worked alongside the vehicles while others made progress in the pits below.

Mustang Assembly

An engine is placed into a Ford Boss 429 Mustang in 1969.

F-150 Assembly

An F-150 body is placed onto the frame at the Louisville Assembly Plant in 1973.

Quality Control

A team performing quality control duties at Dearborn assembly in 1975.

F-Series Inspection

F-Series trucks undergoing inspection at Twin Cities Assembly.

The Modern Era

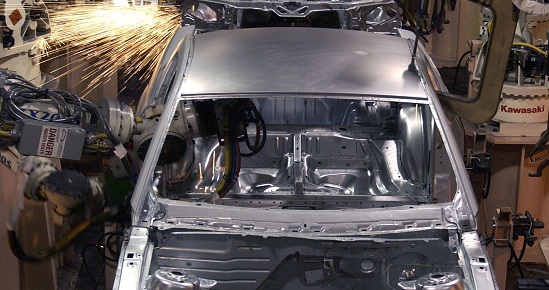

Evolving Mechanization

The mechanization of the assembly line continues to evolve over time, as seen in this 2004 shot of the Ford Mustang being produced at Flat Rock Assembly Plant.

Robotics on the Line

More robotics in place in 2008 at the Fiesta Assembly Line at Ford’s Cologne-Niehl plant in Germany.

People Still Vital

While machines and robots have been introduced into plants to reduce physical stress on workers and increase productivity, people still play the most vital role in bringing a car together.

Healthier Work Environment

Improved processes and ergonomics, as displayed here in 2012 at the Louisville Assembly Plant, have brought workers out of the pits and into a safer, healthier work environment.

Back to Top

Historic Sites

The Rouge

Ford's Rouge Complex is known as an industrial trend-setter in both the 20th and 21st centuries.

Inn on the Tarmac

More than 90 years, the Dearborn Inn was one of the first airport hotels.

Fair Lane: Where The Fords Called "Home"

Henry and Clara Ford's final home, Fair Lane, included a hydroelectric powerhouse and nature areas and is still a landmark today.

Ford Motor Company Lincoln Motor Company

Ford Motor Company Lincoln Motor Company

Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company Lincoln Motor Company